version 2, 11 january 2009 with diagrams, minor corrections and new links (photography and software changes by Kay Moon)

The real difficulty in design is the designer!(I remember Charles Eames saying that in a lecture.)

Originally it was called 'designingityourself'.

Later I made copies for people attending design courses - and they seemed to like it. I think it is time to rewrite it and make it available on the internet.

What follows may seem elementary. It is - but it is more difficult than it looks. To carry it out requires some modesty and a willingness to learn, to change, and to share your thinking with others. Though the text is addressed to an individual most of the methods are intended for collaboration.

Trust life itself; it knows more than any teacher or book.(Johan Wolfgang von Goethe, Selected Poetry, translated with an introduction and notes by David Luke, Libris, London 1999, page 93.)

3. what if I can't think of a solution?

4. what if I have too many ideas?

5. what if my ideas seem good but do not fit 'the problem'?

6. what if my perception of the problem changes?

7. what if I get into a muddle?

8. how can a first attempt be improved?

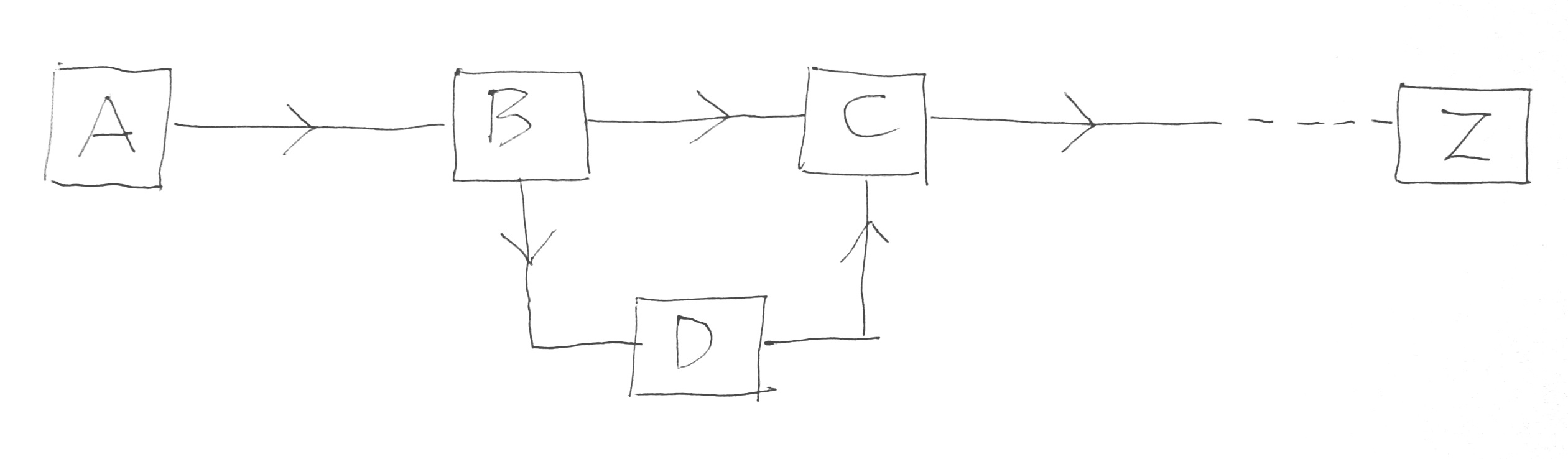

'A' is what you decide to do first (e.g. study an existing design)

'Z' is what you know you will have to do last (e.g. make drawings for production)

'B', 'C', 'D', etc. is whatever pattern of activities you now think will get you from 'A' to 'Z'.

They can be any actions you choose, anything from sketching solutions 'on the back of an envelope', making calculations, or brainstorming, to going for a walk, taking a rest, observing your thoughts when experiencing the design or situation you are trying to improve - what I call existentia.

It is important to choose activities you have confidence in and know you can do. It is also important to include activities which go beyond your experience and which oblige you to learn. 'It was not like me to do that - but I did it, and I am now a different person!'

The complete design process, 'A' to 'Z', is the education you are designing for yourself to teach you all you will need to complete the design. Designing is learning - with yourself and the world as the teacher.

back to c o n t e n t s

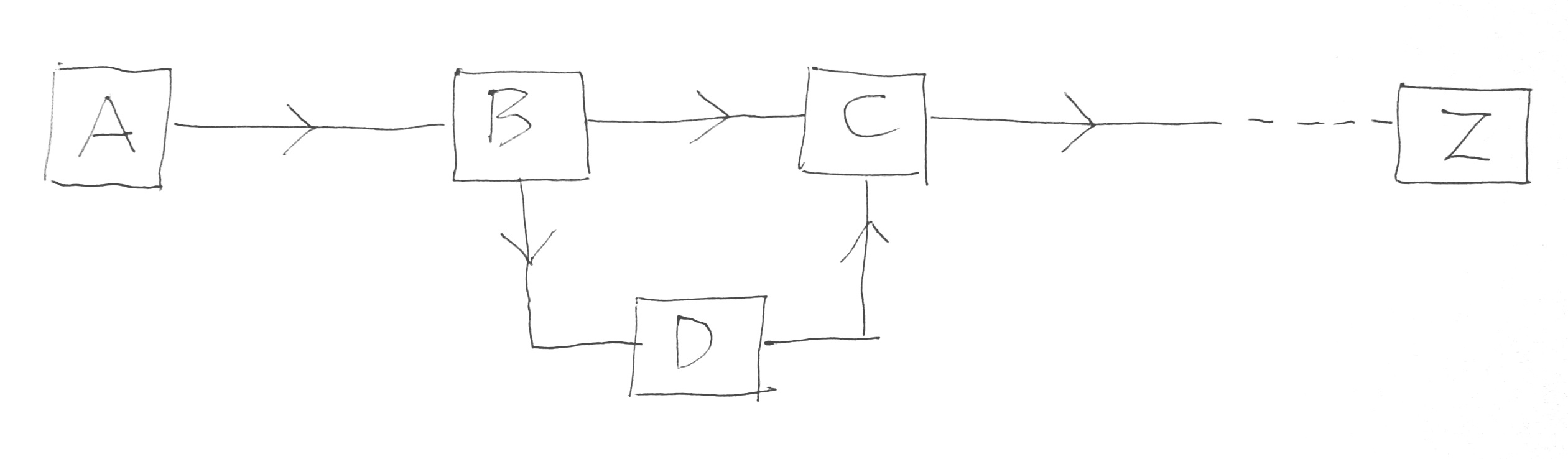

Often one feels like beginning with a sketch or description of what the final design will be like.

Common sense may suggest beginning with a study of what the problem really is.

Both impulses are correct!

A good way to start is:

Expect both problem P and solution S to evolve during the design process:

Expect both problem P and solution S to evolve during the design process:

P1 evolves into P2, P3, P4 etc.

S1 evolves into S2, S3, S4, etc.

See P=S in which I explore the idea that in a creative process the problem and the solution interact... When we encounter the limits and possibilities of what exists we are likely to change our minds and our wishes... The interdependence of the imagined and the real!

back to c o n t e n t s

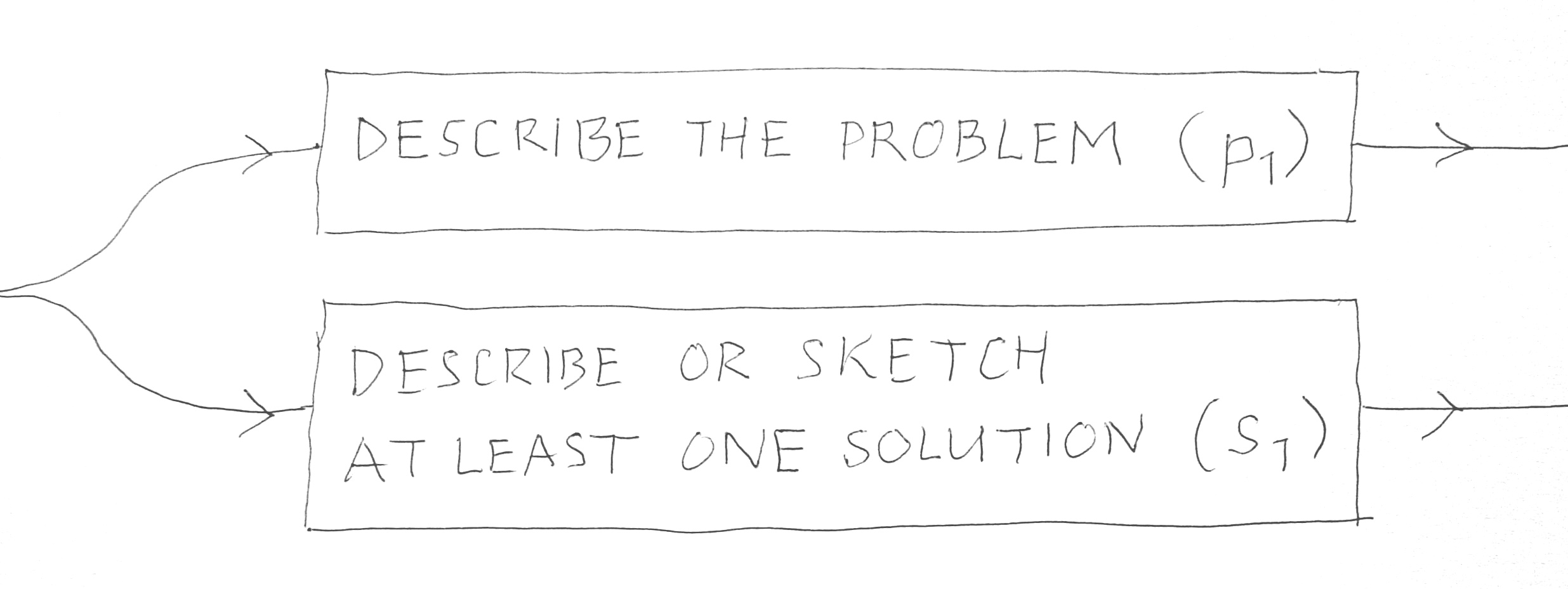

1. Invite a few people (no matter who) to help you.

2. Tell them very clearly what the problem is and ask each of them to write many ways of solving it. Encourage them to write any and every thought that occurs, no matter how crazy, or how obvious, it may seem.

3. Each idea should be written on a separate piece of paper, about 5 cm by 4 so that all the ideas can be sorted out later. (An easy way to make the papers is to halve and tear a piece of A4 paper five times until each piece is A9.)

It is quite possible for five or six people to generate over 100 ideas in twenty minutes or so. The principle of it is to defer evaluation. Normally one does not speak whatever comes to mind - but in brainstorming one does that.

back to c o n t e n t s

With each idea on a separate piece of paper you can sort them into groups or categories. Let these groups, and the names you give them, grow spontaneously, from bottom up. Don't impose a set of categories taken from past experience. You are trying, when designing, to unlearn what you knew before and to feel you way to 'the new', the unknown... but when you find it you may well switch instantaneously to a new concept, 'top down', into which the ideas will acquire new and more promising connections.

Your new grouping or classification should be a conceptual map of the new possibilities that you are discovering.

The naming of groups or categories 1, 2, 3, 4 etc. needs care and imagination - and much time. If possible sleep on it and see if what you have done arouses enthusiasm or indifference next day. If enthusiasm, go ahead immediately. If indifference - reclassify when your mind is ready for it - perhaps in a day or two. The process can take many days, and some depressions, until finally: 'eureka!'

It is best to limit the number of groups or categories to say five to ten. If you have many more than that you cannot easily remember the pattern or 'envisage the whole'.

back to c o n t e n t s

A-type design

design and make small improvements, by improvisation, for a few users during the time of the design process. This can be very informative and satisfying - as well as useful to the people concerned.B-type design

Design and make small improvements for many people, in say a year or two, by designing and marketing a product that makes a difference to users but does not depart too much from what they are used to (the MAYA or 'most advanced yet acceptable' of Raymond Loewy).C-type design

Make big improvements for many people, in say ten to twenty years time, in a futuristic design, assuming that people will by then be thinking differently and will have had time to change their perceptions and habits to take advantage of the new design. You can portray the C-type design in the present not by designing it physically but in fictional accounts of the experience of using it.

back to c o n t e n t s

It is a sign that your original description of the problem (P1) was mistaken.

Working on a design problem is informative. When you are being taught, by your design process, that the problem has been misunderstood it is time to make a new description (P2) that fits your growing knowledge, or rationality.

When this happens you may have to show the people who are commissioning the design work that their interests are best served by evolution of the goal to take account of the latest information to hand. The original goal was chosen in ignorance of what the design process will teach. It is best to seek agreement at the start that goals will be reviewed and changed when necessary.

back to c o n t e n t s

The right step is to

stop designingfor a time and to re-plan the design process.

Persist in re-planning until you have described a new process that brings back your enthusiasm to continue.

back to c o n t e n t s

This is the most popular and effective design method I know. Each person presents a preliminary design which is to be discarded and replaced by a better one based on the affirmative comments of the others.

It is a game played to rules which ensure that each person (in a group of preferably 6-8 people) has equal chance to speak, that each makes only affirmative comments, and that the western tradition of critical argument and defensiveness is replaced by collaboration and encouragement. Here are the rules:

1. There is no leader, only a time keeper*.

2. Each person has 10 minutes in which to present his or her project to the group - and 2 minutes in which to respond to each project of the others.

3. Each responds only positively, beginning with the ritual phrase: 'If I were you I would...' (which must be said each time!). If negative criticisms occur to one they must be rephrased as affirmations e.g. instead of 'I don't like that colour' you might say 'If I were you I would choose a colour that improves visibility'.

4. The person presenting his or her design does not reply to the affirmations but writes every word down in full. This list of affirmations is the valuable result.

5. At the end of each round the person presenting his or her design has 5 minutes in which to reply to the whole round of affirmations. This is not easy to do but it helps one to take a wider view of what one is doing.

6. After the designs have been presented each person makes an improved design based on the affirmations. Many people find the results to be very helpful. It can provoke a better design than one thought oneself capable of.

-speak only in turn round the table ('no comment' is not allowed and repeated comments are to be spoken as it is useful to know when an affirmation occurs to two or more people)

-keep to the time limits

-record all the affirmations of our own design in full (the time keeper should give plenty of time for this)

-do not reply to affirmations until the end of a round (this is a difficult rule to follow when one has the habit of immediate defensiveness - listening without reacting is a skill that is not supported by competitive culture).

The quality of affirmations by students can be equal to that of experienced design teachers. The method is particularly useful when there are too many design students for the teacher to give individual criticisms. It was originally designed and frequently used by students and myself at the Higher Institute of Integrated Product Development, University College, Antwerp.

If you wish to know more see my book Design Methods, second edition, John Wiley & Sons, New York 1992, ISBN 0-442-01182-2 (especially the new material on pages xxii-lxiv).

The Google review of Design Methods includes much of the introductory parts of the book.back to c o n t e n t s

If you wish to reproduce any of this text commercially or in teaching please send a copyright permission request to jcj at publicwriting.net